Unexpected wildlife encounters are one of life’s unsung simple pleasures; even the worst, darkest day can be turned around by the sound of an exquisite, soaring birdsong, the gentle peacefulness of the trees and clouds, or the appearance of a shy animal. In our recent climates of bright sunshine and warmer temperature, it’s no longer a struggle to tear oneself away from a warm fire and book and brave the outdoors, and my time spent wandering in the sunshine was rewarded with a up-close-and-personal encounter with my favourite bird: a common kingfisher.

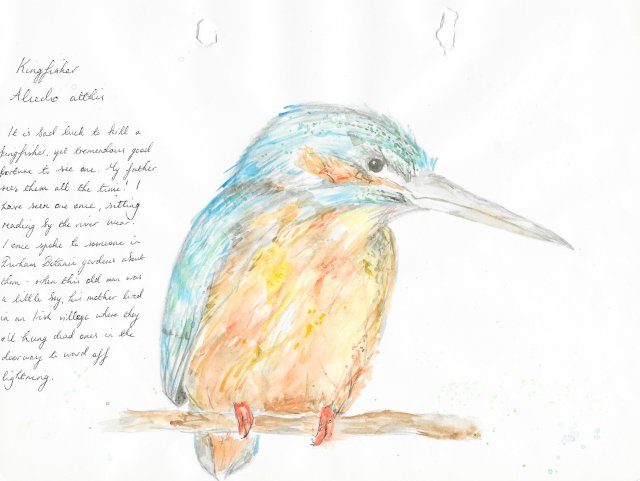

The kingfisher is, for me, a bird full of contradictions; the iridescent, jewel-bright feathers seem unexpected for its tiny, plump frame and disproportionately long beak, and the brutality of its hunting at sharp odds with the precision of its flight and delicacy of movement. They are also very elusive, and often only spotted as a flash of turquoise and amber along a riverbank – even to have only seen this is to count oneself very lucky indeed. Kingfishers are fiercely independent and live very solitary lives; the only time they will even contemplate company is during breeding season, and very few live to see more than one.

I had never seen a kingfisher in the wild until now, having to make do with my dad’s boastful stories about his unending sightings of them along a nearby reservoir. They tend to stick around the banks of rivers, lakes, and streams where there are lots of dense scrubs and bushes, so that they can hunt from overhanging branches. The sight of a kingfisher is a real compliment to the quality of the water, and an indicator of a healthy freshwater ecosystem; they frequent clear, slow-flowing water where prey-visibility and populations are high. I was surprised that my spotting took place by a pond in a local park which I always thought of as being more of a murky, pungent swamp than any kind of wildlife haven, but it makes sense. Thanks to the water’s characteristically stagnant smell and dense, muddy banks, there are never any people or dogs walking by, so the bank-side trees and bushes have grown thick and abundant, and the pond is always full of sticklebacks and tadpoles around this time of year. The kingfisher, furthermore, seems to have grown used to the occasional human visitor; as I said before, most kingfishers sightings I hear about are of flashes of bright colour as the bird darts into thick cover at the sound of oncoming feet, but I was able to stand and watch the bird in branches only a couple of feet away from my head, as it sat perfectly still and watched the water’s surface. It was certainly one of the most beautiful things I have ever seen – there are stories of the birds being stuffed and sewn onto ladies’ hats in Victorian Britain, and (whilst such disregard for living things is always baffling to me) I can understand their appeal as jewel-like decorations.

One of the best things about kingfisher sightings is that you can almost guarantee that you’ll see them again. Kingfishers are highly territorial; since it must eat around 60% of its body weight every day, it is essential for the bird to have control over a suitable stretch of hunting ground. Even when mating pairs for in the autumn, the two birds will retain separate territories and only merge them together in the spring. Any kingfishers encroaching on another’s plot faces brutal consequences; fights between the birds often occur, where one bird will try to drown the other by holding its beak beneath the water. I walk back to park to see the kingfisher every week or so, mainly to watch it hunt; from its perch, or whirring above the water, the kingfisher spots its prey and bobs its head in order to gauge the distance, then dives beneath the water with barely a ripple on the surface. Kingfishers have a third eyelid which allows them to keep their eyes open underwater; once the prey is caught, the bird emerges wing-first from the water, flies back to its perch where it slaps the fish onto a branch to kill it, then swallows it whole, head first. It is all over in about thirty seconds, then the bird is back to watching the surface of the water again, planning its next meal.

Now that April is reluctantly bringing the warm temperatures promised by spring, kingfishers will start laying their eggs in burrows dug into the sides of the riverbanks, which means they’ll be a little easier to spot now that they’re hunting for seven mouths rather than one. You may even hear mating pairs calling to one another in a high-pitched whistle. When the campaign for a national British Bird was launched recently I was hoping with all my heart the kingfisher would win out; I’m not sure what the criteria for specifying ‘britishness’ in a bird is expected to be exactly, but for its colourful beauty and devilish intelligence, there is really no better ambassador than the kingfisher.